Le Locle and La Chaux-de-Fonds – two towns at the heart of time

Who would have thought of building cities in the mountains, 1000 metres above sea level? Especially in a land of pastures and forests beaten by wild gusts of blowing snow, devoid of natural resources and located far off history’s beaten track? Le Locle and La Chaux-de-Fonds are unlikely places, born from the genius and the willpower of determined, imaginative men and women who showed both strength and solidarity.

These “Montagnons” – or mountain people – came from the Val-de-Ruz to find pastures where their cattle could graze. As of the 14th century – perhaps even before – these peasants settled in this rugged countryside and built their first wooden houses in the green expanses. Thanks to privileges granted to them by the Lord of the time, more and more inhabitants established themselves in this austere land, and started building solid stone dwellings. The simple yet elegant architecture of these farms and their rational layout are still admired by those who see them. In these rural buildings, the barn and the living quarters were fitted side by side, under the same roof, which helped to heat the whole interior. Beautiful windows faced south so that the sunlight would enable the inhabitants to try their hand at various crafts.

During the long winter months, these proud mountain people were not inactive, and they took this opportunity to repair their farming tools or to make intricate lace which was sought-after by the aristocratic courts of Europe. This early commercial network would soon come in handy for selling clocks and watches.

© Gérard Benoît à la Guillaume

Le Locle and La Chaux-de-Fonds – two towns at the heart of time

Nestled in the bottom of the valley, La Chaux-de-Fonds spread towards the west and along the north and the south flanks of the hillsides. Le Locle’s topography is more dramatic, and the builders first had to bite into a tormented and mountainous terrain before constructing modern quarters on the surrounding hilltops.

Both towns have preserved their architectural heritage and today, they are a rare testimony to an urban development typical of the 19th and the early 20th centuries, which intricately combined both industry and habitat. In the past century, old apartment buildings have been adapted to meet the needs of modern society, thus avoiding their demolition. Today, the wide and beautiful streets still convey a sense of elegant and colourful harmony. These aspects, among others, are what led to the inscription of the two watchmaking towns on the Unesco World Heritage List in June 2009. Compared to the other World Heritage sites, the choice of La Chaux-de-Fonds and Le Locle may come as a surprise. It is true that these towns don’t reveal their treasures at first glance, and that they must be discovered with an open mind. Most of all, it takes a plunge into their rich industrial history to appreciate their particular urbanism, and to imagine the tenacity and the savoir-faire of those inhabitants who once colonised this wolf-ridden country, and of those who, to this day, still create marvels of timekeeping and refined decorations.

In addition to the urban layout and the industrial production of the region, the character of the “Montagnons” is worth getting to know. Here, there is no place for superficiality, and though it may take a little time, a warm welcome is in store for all who visit.

Today, Le Locle and its 11’000 inhabitants, as well as La Chaux-de-Fonds and its 39’000 residents, are still watchmaking capitals. Now, other industries also fill the workshops, particularly in the fields of micromechanics, microtechnology and medtech; but watchmaking, represented by many prestigious brands, remains to this day the pride of the region.

Nowadays, the modern factories are situated mainly in the outskirts of the towns, in industrial zones where the quality of the environment and of the architecture reflect the high-end spirit which oversees the creation of watches. Watchmakers must always look forward, towards the timepieces of the future, but they never forget the importance of their link with the history of the region. Thus, within the towns, 17th-century farms can be found, like keepers of the past, next to the futuristic factories which shelter these visionaries in the story of timekeeping.

Le Locle and La Chaux-de-Fonds – two towns at the heart of time

From then on, the organisation and the development of La Chaux-de-Fonds and Le Locle were geared to meet the industrial needs of their inhabitants. General progress ensued. In 1887, water was pumped from the source of the river Areuse and conveyed to La Chaux-de-Fonds from the Val-de-Travers thanks to a 20km-long system of aqueducts which brought running water and electricity to the workshops and houses. Education became a priority, as primary schools were built, as well as an industrial (secondary) college and specialised schools. Colleges dedicated to technical studies, applied arts and commerce trained craftsmen, technicians, artists and salesmen, whose knowledge was essential for the local watchmaking industry to be able to compete on an international level.

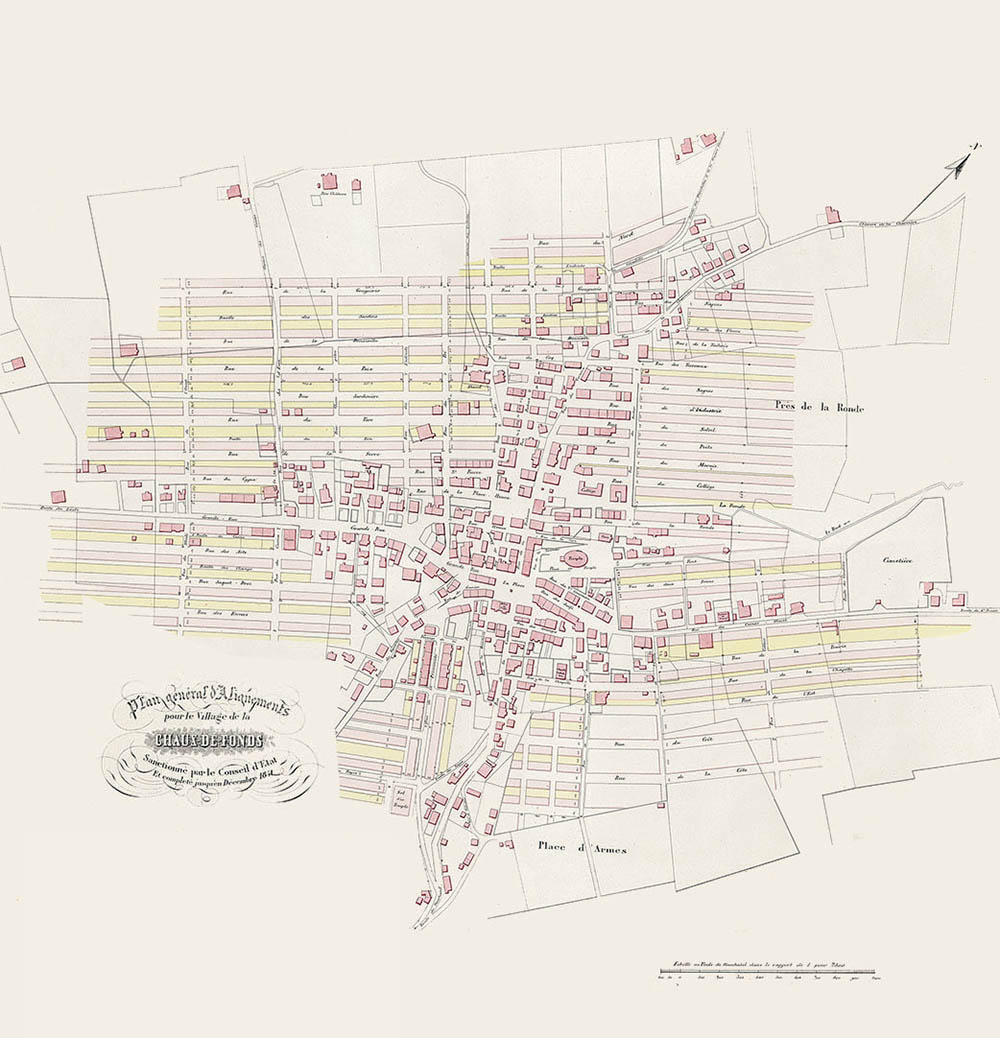

Local urbanism was influenced by this rapid development. From early on, the two towns had suffered numerous horrific fires. The Great Fire of 1794, in La Chaux-de-Fonds, was especially tragic, as the villagers watched two thirds of their homes go up in smoke. Little did they know that the tragedy would lead to the creation of two successive urban schemes which would in turn give birth to the unique grid plan the city is famous for today. In this geometric 19th-century plan, each street gives way to a row of buildings, followed by a row of gardens. This repetitive system turns the rows of buildings into individual entities similar to city blocks, and the streets and gardens ensure a safe distance is maintained between each row. The blocks were built to house working-class families and small workshops whose numerous windows not only let in the sunlight vital for watchmaking, but also met the needs of society’s growing interest in hygiene. The town’s large roads brings to mind the hustle and bustle of the hundreds of delivery-boys who ran to and from the workshops, each carrying a load of one of the many components that fit into the movement of a watch.

This industrial past is still tangible, and it is brought to life thanks to the towns’ homogenous architecture, which avoids monotony thanks to the facades’ variety of colours and detail, and to an ever-present sense of space.

The rapid development of the watchmaking industry, especially between 1880 and 1914, saw buildings neverendingly spring up from the ground. Quality and beauty were a thing of principle, and on each sturdy facade, a multitude of discreet yet ornate decorations is on show for those with attentive eyes. The turn of the 20th century also saw the proliferation of elegant factories and opulent mansions which displayed the prosperity and the artistic taste of the towns’ many “watchmaking-directors”.

© Vincent Bourrut

Le Locle and La Chaux-de-Fonds – two towns at the heart of time

When the first timepieces appeared, these ingenious artisans soon learned to dismantle and repair them, and to create their own. The farmers were curious and open to progress. They were also used to depending on their strengths alone to overcome the hardships related to the stark and inhospitable land they inhabited. Watchmaking here was born from necessity and from the soon-to-be farmer-watchmakers’ will to survive. Soon, the peasants of old became masters in the measurement of time. Most of them left their homes and headed for the two nearest villages that were developing fast: Le Locle, located in the marshy valley of the Bied; and La Chaux-de-Fonds, built close to the source of a small river called La Ronde.

Le Locle’s name derives from the Latin word lacus (lake), which refers to the abundant water that lies within its marshy soil. La Chaux-de-Fonds, on the other hand, has little access to drinking water. The locality owes its name to the Latin words calmis (Chaux), or “high-up and uncultivated pastures”, and fons (Fonds), which means “fountain”. Another version suggests that “Fonds”refers to the first inhabitants of the nearby village of Fontaines. Thus, the name of the town means either the pasture near the fountain or the neighbours’ field!

The local talent for watchmaking enabled both villages to grow into towns. In the 1800s, the tick-tock of clocks and watches rang out like the beating of a heart.